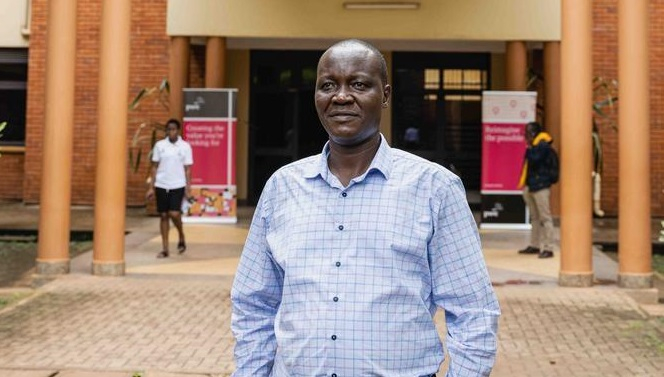

Esther Ruth Mbabazi für VolkswagenStiftung

Trained as a mechanical engineer, the Kampala-based researcher Peter W. Olupot has spent the last decade finding ways to produce affordable water purification systems using rice husks, a common byproduct of rice production.

It takes a certain talent to find world-changing value in something most consider waste. Peter W. Olupot has that talent. A professor of mechanical engineering at Makerere University in Kampala, the capital of Uganda, Olupot has spent the last decade finding ways to produce affordable water purification systems using rice husks, a common byproduct of rice production.

Rice is an increasingly important crop in Uganda, where the government has pushed farmers to grow the crop for both domestic consumption and export. "There’s been a concerted effort to promote rice growing and cultivation," Olupot says: Ugandan farmers grew more than 700,000 tons of rice last year.

Troublesome leftovers

But all that rice creates troublesome leftovers. To process the grains, rice mills must first remove their husks. In Uganda, "there’s no known good application for rice husks," Olupot says. "Normally they just get dumped behind the rice mills." In the worst case, the mounds of rice husks catch fire, sometimes smoldering for months and choking nearby villages with their smoke.

That hasn’t stopped enterprising Ugandans from trying to find ways to use the husks. A decade ago, for example, the owner of a local rice mill came to the mechanical engineering department at Makerere University with a problem: They were trying to press rice husks into briquettes for use in domestic cooking, but the extrusion machine used to press the husks kept breaking down. The briquettes themselves, meanwhile, were poor quality compared to those made from wood charcoal. Olupot’s supervisor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the time asked him to investigate the factory’s metal machinery for potential weaknesses. But Olupot soon became fascinated not by the machine parts but by the rice husks passing through them.

Rice husks remain as waste after hulling.

"I was interested in the properties of the material they were extruding," he says. "I thought, ‘maybe the rice husk are the source of the problem.’"

Tough material

Diving into scientific literature from different fields and talking with rice growers and processors, Olupot quickly learned rice husks posed a particularly tough challenge: The tough outer membranes of rice grains contain more than 80% silicon dioxide, essentially the same substance as the quartz in sand. "It’s very abrasive," Olupot says. "It was causing a lot of wear on the machines." Meanwhile, briquettes made with the rice husks burned slowly and produced a lot of ash because of all the minerals they contained.

Rice cultivation also dominates agriculture in Zirobwe, close to Uganda's capital Kampala.

Rice husks are tough to digest, too, making them unsuitable for reuse as animal feed; they decompose slowly, making for poor compost. One of the few uses Ugandan rice growers have found for the rice husks is animal bedding, hardly a high-value product. "I wondered, what were some alternative uses?" Olupot says.

A transdisciplinary journey

That thought launched a decade-long quest to make the most of rice husks, a journey that exemplifies the concept of transdisciplinarity . Supported by grants from the Volkswagen Foundation since 2015, Olupot’s research resulted in a way to transform the discarded husks into activated carbon, the key component of affordable water purification systems. Along the way he worked with chemical and biosystems engineers, consulted the leaders of local marketplaces in Uganda and talked with farmers and rice mill owners about their experience with rice husks.

Peter W. Olupot teaches and researches at the College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology at Makerere University in Kampala.

Purifying water with activated carbon

Under a microscope, grains of activated carbon are full of holes and pores, like a black honeycomb or sponge, giving it lots of surface: A gram of activated carbon can have a stunning 3,000 square meters of surface area. When water is passed through, impurities – from organic compounds to chlorine and heavy metals – bind with the surface of the activated carbon. "What’s left is pure water which can be subjected to disinfection for extermination of bacteria," Olupot says. The activated carbon found in most water purifiers is made from wood or coconut shells treated with chemicals and subjected to very hot temperatures.

With support from the Volkswagen Foundation as part of its program "Knowledge for Tomorrow – Cooperative Research in sub-Saharan Africa" , Olupot combed the scientific literature and tinkering with ways to transform rice husks into activated carbon.

Working with colleagues in the agricultural sciences department at the University of Kassel in Germany, he eventually hit on a recipe that separated the silicon dioxide in rice husks from the organic material using common chemicals, including easily-obtainable sodium hydroxide, or lye. By chemically treating and then heating the carbon left over, he was able to come up with activated carbon that could compete with varieties made from burning wood.

Activated carbon has a large surface area: One gram can have a surface area of 3,000 square metres - therefore the carbon can bind impurities very well.

Widespread interest

The resulting publications have been cited hundreds of times in just a few years, showing that there’s widespread interest in the process. Olupot’s rice husk research got another boost in 2020, when the COVID pandemic prompted researchers worldwide to come up with transdisciplinary solutions to the global crisis. Olupot knew that rural and impoverished parts of Uganda had trouble accessing clean running water, a key part of keeping hands clean and disease-free. "There was a call from the Volkswagen Foundation to come up with solutions," Olupot recalls, "and I proposed developing technology to optimize hand-washing."

It’s also useful for schools, or in densely populated areas.

At the time, Uganda was requiring people to wash their hands before entering public spaces like marketplaces or pharmacies. Much of the wastewater was dumped after one use, often killing vegetation or contributing to unsanitary conditions.

From idea to prototype

In the space of a year, Olupot built and patented a prototype handwashing station that passed water through layers of activated carbon derived from rice husks. After people used it to wash their hands, the purified water could be recycled, making it suitable for villages without access to running water. For an extra layer of safety a solar panel on top generated enough electricity to power an ultraviolet light that killed any bacteria that made it through the activated carbon. "It’s also useful for schools, or in densely populated areas," Olupot says.

Peter W. Olupot (right) and his colleagues Joel Wakatuntu and Tonny Kavuma (left) at the prototype of the handwashing station.

Olupot's road to research on rice husks wasn't one he expected to follow when applying to university. A talented math and science student, he hoped to study electrical engineering -- but a government grant for students pursuing mechanical engineering tempted him to switch fields at the last moment. It was a move he was grateful for later. "I had more opportunities for employment as a mechanical engineer," he says.

Though the Foundation’s funding has been key in making his discoveries possible, "the Volkswagen Foundation has helped me in many ways," Olupot says. Courses and mentorship in grant-writing and public outreach have increased the impact of his research. He credits the courses in management provided by the foundation with making it possible to expand his lab to supervise 8 PhD students. "That has helped my research immensely," Olupot says.

Other neglected sources of biomass

The experience and knowledge Olupot has gained from research on rice husks has led to a wider interest in transforming neglected sources of biomass – from corn cobs to rice husks – into carbon that can be incorporated into other products. "Ideally, the concept was to use unconventional materials, like rice husks," Olupot says. "Cutting trees down to make charcoal is an environmental concern."

In a rice mill in Zirobwe, employee Mulopa Davis turns the freshly harvested rice, which is dried in the sun and regularly turned by hand. The rice grains are then easy to peel and can be stored and sold without the risk of mold.

On the way to future applications

One application he hopes to pursue in the future is so-called "green steel," which uses carbon derived from biomass as part of the production process. Ideally, rice husks could contribute to that process, too. "We should be looking harder at what we can do with carbon from biomass," he says.

We should be looking harder at what we can do with carbon from biomass

Olupot has applied for a patent for his solar powered, rice husk-based hand-washing station. Although the urgency of COVID has faded, there’s still a need for the technology in places where plumbing and other infrastructure is scarce, from refugee camps to schools in rural villages. And Ugandan officials are exploring activated carbon as a part of water treatment thanks to its ability to filter out heavy metals. "Some places don’t have the luxury of running water," Olupot says. "We still have a lot of communities that could benefit from this technology."