Patricia Kühfuss

A chance in the pandemic – learning from each other

What are the consequences of corona-related mobility restrictions and who is affected and in what way? In close cooperation, scholars from Germany, South Korea, South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo want to conduct comparative research on this issue.

People all over the world are currently facing an experience that is unprecedented on such a scale: a global pandemic whose outcome and end are not foreseeable. Ebola, malaria, SARS – these continue to be devastating epidemics that mainly occur in Africa and Asia. Corona, however, affects everybody everywhere – bringing about drastic changes to their lives by limiting social contacts and mobility.

Populations around the world should perceive the Corona pandemic as a chance to take a truly global view on health issues for the first time

Some countries seem to be coping better than others, at least in some respects: South Korea, for example, which has already had to deal with the SARS-CoV-1 virus and the MERS virus. Countries like South Africa or the Democratic Republic of Congo have also experienced dangerous epidemics with HIV/AIDS and Ebola respectively.

"Populations around the world should perceive the Corona pandemic as a chance to take a truly global view on health issues for the first time and to benefit from the experience of others in containing the virus, for example through mobility restrictions. We should ask ourselves what could be transferred to our own country as well as what is not transferable – and how we can jointly master challenges such as the distribution of the vaccine," says social and cultural anthropologist Hansjörg Dilger, professor at the Free University of Berlin. So far, he says, a "together" of global North and global South is hardly discernible.

Who bears what consequences?

Together with partners from South Korea, South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo as well as at the Universities of Bayreuth and Halle, Dilger wants to realize the project "Mobility Regimes of Pandemic Preparedness and Response: The Case of Covid-19", which, due to its comparative perspective, is expected to yield interesting results. The ethnographic study aims to examine the different approaches to restricting and monitoring mobility. It raises the question of the social, economic and political consequences and examines what individual or collective price has to be paid for the frequently harsh restrictions on freedom of movement.

With this in view, people in the countries participating in the project are interviewed about the changes taking place in their everyday lives, and networks are being established with stakeholders from NGOs, academia and politics. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, women's informal trade networks have been strongly affected by regional border closures with Rwanda. This aspect is being researched by Prof. Dr. Nene Morisho, Director of the Pole Institute in Goma. South Africa could also serve as a good example of a society in which the great social inequality is exacerbated by Covid-19, says Hansjörg Dilger.

The view to South Africa

"At the same time, South Africa is a state that functions relatively well," explains anthropologist and project partner Julia Hornberger, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. "While there is corruption, incompetence and many shortcomings, state institutions and structures permeate society even to the remotest regions, and aid reaches large parts of the population. These strong state structures have led to South Africa not only announcing a very tough lockdown, but also to it being enforced – especially from March to June 2020."

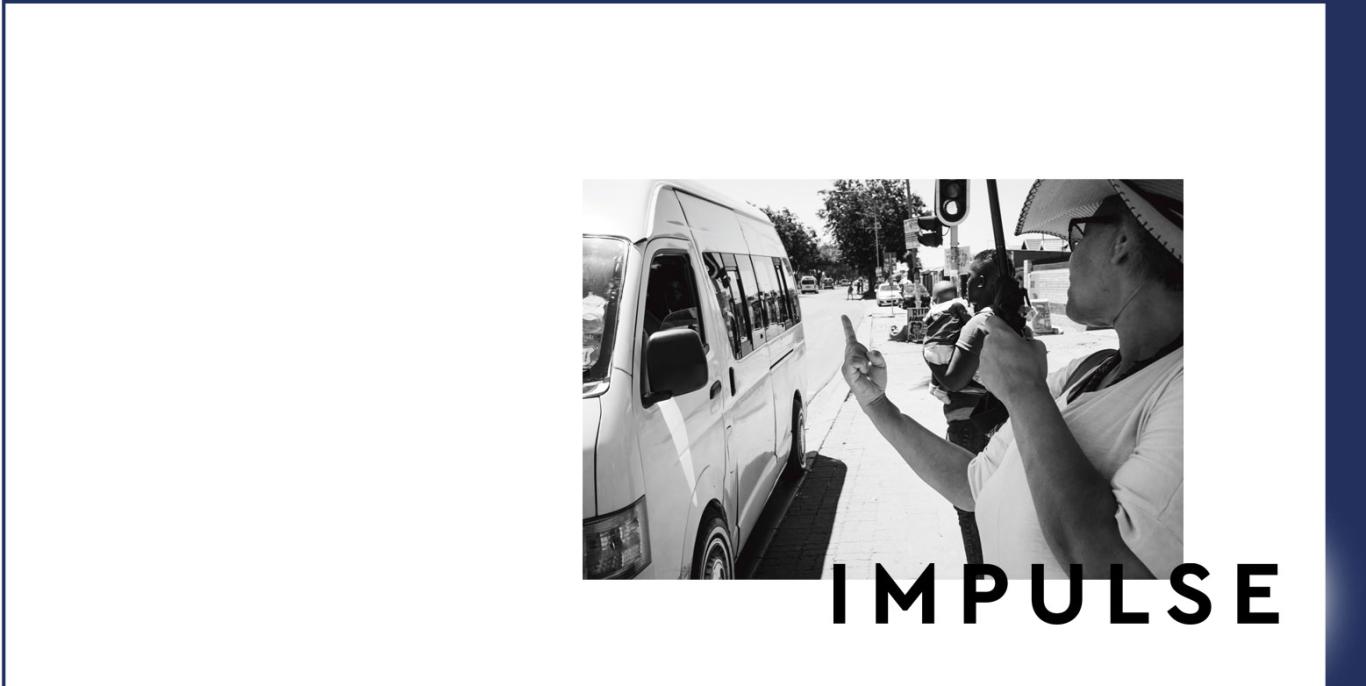

A man in Johannesburg, South Africa, uses hand signals to show a minibus which direction he wants to go.

A combination of fear of the police and fear of the virus led to much of the population submitting to and obeying the lockdown regulations without protest, Hornberger said. The fear of the police, who often act outside the law, is rooted in apartheid history. The fear of Corona, on the other hand, is connected to the experience with HIV/AIDS; the awareness of the deadly power and terrible consequences of viruses is very present.

Hansjörg Dilger finds it striking just how quickly informal organizations have formed in the poorer areas of South Africa, which distribute food parcels, among other things. "Strong networks of solidarity are needed particularly in those areas where the pandemic has had a devastating impact on individual social groups such as unlicensed informal traders who are no longer able to secure their daily income due to the lockdown and who receive no state support. Civil society support also emerged in South Africa where people were criminalized by the state and evicted from informal settlements," he says.

Of humanity and strict enforcement

"These initiatives are sometimes more effective than the state itself," Julia Hornberger reports. "Most South Africans, especially black South Africans, are no strangers to the idea of restricting one's own desires in order to help others. Principles like 'black tax' (sharing one's income with others) and 'ubuntu' (humanity and solidarity) are based on subordinating one's own individual freedom to the needs of the family or the group," the anthropologist explains.

South Korea, on the other hand, is pursuing a different strategy of its own. According to Bo Kyeong Seo, professor of anthropology at Yonsei University, her country was very effective in identifying and isolating individual cases and clusters of infection at an early stage. But contact tracing and cohort isolation of specific groups also have their downsides. "Although the 'test, trace, isolate' strategy is a much less severe measure than blocking at the national level, it has severely affected the mobility and thus the lives of individuals, especially vulnerable groups such as the disabled and the elderly."

Hansjörg Dilger also sees the effectiveness of South Korea's strategy of strict tracking and isolation of infection cases, but he says there are of course limits to the transferability of such "recipes for success": "It is unthinkable in Germany, for instance, that the police or employees of the health department would turn up unannounced in private homes to enforce measures. But that is no reason not to learn from the experiences of others in order to develop your own, more suitable concepts."